The Best American Magazine Writing 2017 Read online

Page 7

David Goldsmith, president of the council, told me he didn’t believe that creating low-income set-asides in only one school made sense; he is working to create a plan that would try to integrate the schools in the entire district that includes PS 8 and PS 307. But Benjamin Greene, who voted against the rezoning because it did not guarantee that half of the seats would remain for low-income children, said: “We cannot sit around and wait until somebody decides on this wonderful formula districtwide. We have to preserve these schools one at a time.”

In voting for the rezoning, the council touted its bravery and boldness in choosing integration in a system that seemed opposed to it. “With the eyes of the nation upon us,” Goldsmith began. “Voting ‘yes’ means we refuse to be victims of the past. We are ready to do this. The time is now. We owe this to our children.”

But the decision felt more like a victory for the status quo. This rezoning did not occur because it was in the best interests of PS 307’s black and Latino children but because it served the interests of the wealthy, white parents of Brooklyn Heights. PS 8 will only get whiter and more exclusive: the council failed to mention at the meeting that the plan would send future students from the only three Farragut buildings that had been zoned for PS 8 to PS 307, ultimately removing almost all the low-income students from PS 8 and turning it into one of the most affluent schools in the city. The Department of Education projects that within six years, PS 8 could be three-quarters white in a school system where only one-seventh of the kids are white.

PS 307 may eventually look similar. Without seats guaranteed for low-income children, and with an increasing white population in the zone, the school may flip and become mostly white and overcrowded. Farragut parents worry that at that point, the project’s children, like those at PS 8, could be zoned out of their own school. A decade from now, integration advocates could be lamenting how PS 307 went from nearly all black and Latino to being integrated for a period to heavily white.

That transition isn’t going to happen immediately, so some Dumbo parents have threatened to move or enroll their children in private schools. Others are struggling over what to do. By allowing such vast disparities between public schools—racially, socioeconomically, and academically—this city has made integration the hardest choice.

“You’re not living in Brooklyn if you don’t want to have a diverse system around your kid,” Michael Jones, who lives in Brooklyn Heights and considered sending his twins to PS 307 for pre-K because PS 8 no longer offered it, told me over coffee. “You want it to be multicultural. You know, if you didn’t want that, you’d be in private school, or you would be in a different area. So, we’re all living in Brooklyn because we want that to be part of the upbringing. But you can understand how a parent might look at it and go, ‘While I want diversity, I don’t want profound imbalance.’ ” He thought about what it would have meant for his boys to be among the few middle-class children in PS 307. “We could look at it and see there is probably going to be a clash of some kind,” he said. “My kid’s not an experiment.” In the end, he felt that he could not take a chance on his children’s education and sent them to private preschool; they now go to PS 8.

This sense of helplessness in the face of such entrenched segregation is what makes so alluring the notion, embraced by liberals and conservatives, that we can address school inequality not with integration but by giving poor, segregated schools more resources and demanding of them more accountability. True integration, true equality, requires a surrendering of advantage, and when it comes to our own children, that can feel almost unnatural. Najya’s first two years in public school helped me understand this better than I ever had before. Even Kenneth Clark, the psychologist whose research showed the debilitating effects of segregation on black children, chose not to enroll his children in the segregated schools he was fighting against. “My children,” he said, “only have one life.” But so do the children relegated to this city’s segregated schools. They have only one life, too.

New York

FINALIST—REPORTING

Gabriel Sherman’s reporting on the fall of Roger Ailes, the chairman and CEO of Fox News—including more than a dozen articles published online in New York’s “Daily Intelligencer”—culminated in the cover story of the September 5, 2016, print issue. Headlined “The Revenge of Roger’s Angels” (the cover line was the more evocative “Fox and Prey”), the story was, the Ellie judges said, “an astonishing example of what one tenacious reporter can accomplish despite undisguised hostility and attempted intimidation.” Sherman knew the subject well—his biography of Ailes, The Loudest Voice in the Room, was published in 2014. Less than nine months after this story was published, Ailes was dead, the victim of a brain injury.

Gabriel Sherman

The Revenge of Roger’s Angels

It took fifteen days to end the mighty twenty-year reign of Roger Ailes at Fox News, one of the most storied runs in media and political history. Ailes built not just a conservative cable news channel but something like a fourth branch of government; a propaganda arm for the GOP; an organization that determined Republican presidential candidates, sold wars, and decided the issues of the day for two million viewers. That the place turned out to be rife with grotesque abuses of power has left even its liberal critics stunned. More than two dozen women have come forward to accuse Ailes of sexual harassment, and what they have exposed is both a culture of misogyny and one of corruption and surveillance, smear campaigns and hush money, with implications reaching far wider than one disturbed man at the top.

It began, of course, with a lawsuit. Of all the people who might have brought down Ailes, the former Fox and Friends anchor Gretchen Carlson was among the least likely. A fifty-year-old former Miss America, she was the archetypal Fox anchor: blonde, right-wing, proudly anti-intellectual. A memorable Daily Show clip showed Carlson saying she needed to Google the words czar and ignoramus. But television is a deceptive medium. Off-camera, Carlson is a Stanford- and Oxford-educated feminist who chafed at the culture of Fox News. When Ailes made harassing comments to her about her legs and suggested she wear tight-fitting outfits after she joined the network in 2005, she tried to ignore him. But eventually he pushed her too far. When Carlson complained to her supervisor in 2009 about her cohost Steve Doocy, who she said condescended to her on and off the air, Ailes responded that she was “a man hater” and a “killer” who “needed to get along with the boys.” After this conversation, Carlson says, her role on the show diminished. In September 2013, Ailes demoted her from the morning show Fox and Friends to the lower-rated two p.m. time slot.

Carlson knew her situation was far from unique: It was common knowledge at Fox that Ailes frequently made inappropriate comments to women in private meetings and asked them to twirl around so he could examine their figures, and there were persistent rumors that Ailes propositioned female employees for sexual favors. The culture of fear at Fox was such that no one would dare come forward. Ailes was notoriously paranoid and secretive—he built a multiroom security bunker under his home and kept a gun in his Fox office, according to Vanity Fair—and he demanded absolute loyalty from those who worked for him. He was known for monitoring employee e-mails and phone conversations and hiring private investigators. “Watch out for the enemy within,” he told Fox’s staff during one companywide meeting.

Taking on Ailes was dangerous, but Carlson was determined to fight back. She settled on a simple strategy: She would turn the tables on his surveillance. Beginning in 2014, according to a person familiar with the lawsuit, Carlson brought her iPhone to meetings in Ailes’s office and secretly recorded him saying the kinds of things he’d been saying to her all along. “I think you and I should have had a sexual relationship a long time ago, and then you’d be good and better and I’d be good and better. Sometimes problems are easier to solve” that way, he said in one conversation. “I’m sure you can do sweet nothings when you want to,” he said another time.

After more than a

year of taping, she had captured numerous incidents of sexual harassment. Carlson’s husband, sports agent Casey Close, put her in touch with his lawyer Martin Hyman, who introduced her to employment attorney Nancy Erika Smith. Smith had won a sexual-harassment settlement in 2008 for a woman who sued former New Jersey acting governor Donald DiFranceso. “I hate bullies,” Smith told me. “I became a lawyer to fight bullies.” But this was riskier than any case she’d tried. Carlson’s Fox contract had a clause that mandated that employment disputes be resolved in private arbitration—which meant Carlson’s case could be thrown out and Smith herself could be sued for millions for filing.

Carlson’s team decided to circumvent the clause by suing Ailes personally rather than Fox News. They hoped that with the element of surprise, they would be able to prevent Fox from launching a preemptive suit that forced them into arbitration. The plan was to file in September 2016 in New Jersey Superior Court (Ailes owns a home in Cresskill, New Jersey). But their timetable was pushed up when, on the afternoon of June 23, Carlson was called into a meeting with Fox general counsel Dianne Brandi and senior executive VP Bill Shine, and fired the day her contract expired. Smith, bedridden following surgery for a severed hamstring, raced to get the suit ready. Over the Fourth of July weekend, Smith instructed an IT technician to install software on her firm’s network and Carlson’s electronic devices to prevent the use of spyware by Fox. “We didn’t want to be hacked,” Smith said. They filed their lawsuit on July 6.

Carlson and Smith were well aware that suing Ailes for sexual harassment would be big news in a post-Cosby media culture that had become more sensitive to women claiming harassment; still, they were anxious about going up against such a powerful adversary. What they couldn’t have known was that Ailes’s position at Fox was already much more precarious than ever before.

When Carlson filed her suit, 21st Century Fox executive chairman Rupert Murdoch and his sons, James and Lachlan, were in Sun Valley, Idaho, attending the annual Allen & Company media conference. James and Lachlan, who were not fans of Ailes’s, had been taking on bigger and bigger roles in the company in recent years (technically, and much to his irritation, Ailes has reported to them since June 2015), and they were quick to recognize the suit as both a big problem—and an opportunity. Within hours, the Murdoch heirs persuaded their eighty-five-year-old father, who historically has been loath to undercut Ailes publicly, to release a statement saying, “We take these matters seriously.” They also persuaded Rupert to hire the law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison to conduct an internal investigation into the matter. Making things look worse for Ailes, three days after Carlson’s suit was filed, New York published the accounts of six other women who claimed to have been harassed by Ailes over the course of three decades.

A few hours after the New York report, Ailes held an emergency meeting with longtime friend Rudy Giuliani and lawyer Marc Mukasey at his home in Garrison, New York, according to a high-level Fox source. Ailes vehemently denied the allegations. The next morning, Ailes and his wife, Elizabeth, turned his second-floor office at Fox News into a war room. “It’s all bullshit! We have to get in front of this,” he said to executives. “This is not about money. This is about his legacy,” said Elizabeth, according to a Fox source. As part of his counteroffensive, Ailes rallied Fox News employees to defend him in the press. Fox and Friends host Ainsley Earhardt called Ailes a “family man”; Fox Business anchor Neil Cavuto wrote, reportedly of his own volition, an op-ed labeling Ailes’s accusers “sick.” Ailes’s legal team attempted to intimidate a former Fox correspondent named Rudi Bakhtiar who spoke to New York about her harassment.

Ailes told executives that he was being persecuted by the liberal media and by the Murdoch sons. According to a high-level source inside the company, Ailes complained to 21st Century Fox general counsel Gerson Zweifach that James, whose wife had worked for the Clinton Foundation, was trying to get rid of him in order to help elect Hillary Clinton. At one point, Ailes threatened to fly to France, where Rupert was vacationing with his wife, Jerry Hall, in an effort to save his job. Perhaps Murdoch told him not to bother, because the trip never happened.

According to a person close to the Murdochs, Rupert’s first instinct was to protect Ailes, who had worked for him for two decades. The elder Murdoch can be extremely loyal to executives who run his companies, even when they cross the line. (The most famous example of this is Sun editor Rebekah Brooks, whom he kept in the fold after the UK phone-hacking scandal.) Also, Ailes has made the Murdochs a lot of money—Fox News generates more than $1 billion annually, which accounts for 20 percent of 21st Century Fox’s profits—and Rupert worried that perhaps only Ailes could run the network so successfully. “Rupert is in the clouds; he didn’t appreciate how toxic an environment it was that Ailes created,” a person close to the Murdochs said. “If the money hadn’t been so good, then maybe they would have asked questions.”

Beyond the James and Lachlan factor, the relationship between Murdoch and Ailes was becoming strained: Murdoch didn’t like that Ailes was putting Fox so squarely behind the candidacy of Donald Trump. And he had begun to worry less about whether Fox could endure without its creator. (In recent years, Ailes had taken extended health leaves from Fox and the ratings held.) Now Ailes had made himself a true liability: More than two dozen Fox News women told the Paul, Weiss lawyers about their harassment in graphic terms. The most significant of the accusers was Megyn Kelly, who is in contract negotiations with Fox and is considered by the Murdochs to be the future of the network. So important to Fox is Kelly that Lachlan personally approved her reported $6 million book advance from Murdoch-controlled publisher HarperCollins, according to two sources.

As the inevitability of an ouster became clear, chaos engulfed Ailes’s team. After news broke on the afternoon of July 19 that Kelly had come forward, Ailes’s lawyer Susan Estrich tried to send Ailes’s denial to Drudge but mistakenly e-mailed a draft of Ailes’s proposed severance deal, which Drudge, briefly, published instead. Also that day, Ailes’s allies claimed to conservative news site Breitbart that fifty of Fox’s biggest personalities were prepared to quit if Ailes was removed, though in reality there was no such pact. That evening, Murdoch used one of his own press organs to fire back, with the New York Post tweeting the cover of the next day’s paper featuring Ailes’s picture and news that “the end is near for Roger Ailes.”

Indeed, that evening Ailes was banned from Fox News headquarters, his company e-mail and phone shut off. On the afternoon of July 21, a few hours before Trump was to accept the Republican nomination in Cleveland, Murdoch summoned Ailes to his New York penthouse to work out a severance deal. James had wanted Ailes to be fired for cause, according to a person close to the Murdochs, but after reviewing his contract, Rupert decided to pay him $40 million and retain him as an “adviser.” Ailes, in turn, agreed to a multiyear noncompete clause that prevents him from going to a rival network (but, notably, not to a political campaign). Murdoch assured Ailes that, as acting CEO of Fox News, he would protect the channel’s conservative voice. “I’m here, and I’m in charge,” Murdoch told Fox staffers later that afternoon with Lachlan at his side (James had gone to Europe on a business trip). That night, Rupert and Lachlan discussed the extraordinary turn of events over drinks at Eleven Madison Park.

The Murdochs must have hoped that by acting swiftly to remove Ailes, they had averted a bigger crisis. But over the coming days, harassment allegations from more women would make it clear that the problem was not limited to Ailes but included those who enabled him—both the loyal deputies who surrounded him at Fox News and those at 21st Century Fox who turned a blind eye. “Fox News masquerades as a defender of traditional family values,” claimed the lawsuit of Fox anchor Andrea Tantaros, who says she was demoted and smeared in the press after she rebuffed sexual advances from Ailes, “but behind the scenes, it operates like a sex-fueled, Playboy Mansion–like cult, steeped in intimidation, indecency and misogyny.”

&n

bsp; • • •

Murdoch knew Ailes was a risky hire when he brought him in to start Fox News in 1996. Ailes had just been forced out as president of CNBC under circumstances that would foreshadow his problems at Fox.

While his volcanic temper, paranoia, and ruthlessness were part of what made Ailes among the best television producers and political operatives of his generation, those same attributes prevented him from functioning in a corporate environment. He hadn’t lasted in a job for more than a few years. “I have been through about twelve train wrecks in my career. Somehow, I always walk away,” he told an NBC executive.

By all accounts, Ailes had been a management disaster from the moment he arrived at NBC in 1993. But by 1995, things had reached a breaking point. In October of that year, NBC hired the law firm Proskauer Rose to conduct an internal investigation after then–NBC executive David Zaslav told human resources that Ailes had called him a “little fucking Jew prick” in front of a witness.

Zaslav told Proskauer investigators he feared for his safety. “I view Ailes as a very, very dangerous man. I take his threats to do physical harm to me very, very seriously … I feel endangered both at work and at home,” he said, according to NBC documents, which I first published in my 2014 biography of Ailes. CNBC executive Andy Friendly also filed complaints. “I along with several of my most talented colleagues have and continue to feel emotional and even physical fear dealing with this man every day,” he wrote. The Proskauer report chronicled Ailes’s “history of abusive, offensive, and intimidating statements/threats and personal attacks.” Ailes left NBC less than three months later.

What NBC considered fireable offenses, Murdoch saw as competitive advantages. He hired Ailes to help achieve a goal that had eluded Murdoch for a decade: busting CNN’s cable-news monopoly. Back in the midnineties, no one thought it could be done. “I’m looking forward to squishing Rupert like a bug,” CNN founder Ted Turner boasted at an industry conference. But Ailes recognized how key wedge issues—race, religion, class—could turn conservative voters into loyal viewers. By January 2002, Fox News had surpassed CNN as the highest-rated cable-news channel. But Ailes’s success went beyond ratings: The rise of Fox News provided Murdoch with the political influence in the United States that he already wielded in Australia and the United Kingdom. And by merging news, politics, and entertainment in such an overt way, Ailes was able to personally shape the national conversation and political fortunes as no one ever had before. It is not a stretch to argue that Ailes is largely responsible for, among other things, the selling of the Iraq War, the Swift-boating of John Kerry, the rise of the Tea Party, the sticking power of a host of Clinton scandals, and the purported illegitimacy of Barack Obama’s presidency.

The Best American Magazine Writing 2020

The Best American Magazine Writing 2020 The Best American Magazine Writing 2016

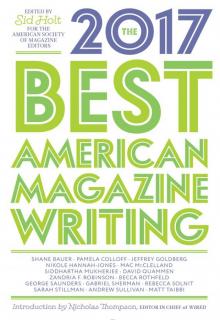

The Best American Magazine Writing 2016 The Best American Magazine Writing 2017

The Best American Magazine Writing 2017