The Best American Magazine Writing 2017 Read online

Page 5

In New York City, home to the largest black population in the country, the decision was celebrated by many liberals as the final strike against school segregation in the “backward” South. But Kenneth Clark, the first black person to earn a doctorate in psychology at Columbia University and to hold a permanent professorship at City College of New York, was quick to dismiss Northern righteousness on race matters. At a meeting of the Urban League around the time of the decision, he charged that though New York had no law requiring segregation, it intentionally separated its students by assigning them to schools based on their race or building schools deep in segregated neighborhoods. In many cases, Clark said, black children were attending schools that were worse than those attended by their black counterparts in the South.

Clark’s words shamed proudly progressive white New Yorkers and embarrassed those overseeing the nation’s largest school system. The New York City Board of Education released a forceful statement promising to integrate its schools: “Segregated, racially homogeneous schools damage the personality of minority-group children. These schools decrease their motivation and thus impair their ability to learn. White children are also damaged. Public education in a racially homogeneous setting is socially unrealistic and blocks the attainment of the goals of democratic education, whether this segregation occurs by law or by fact.” The head of the Board of Education undertook an investigation in 1955 that confirmed the widespread separation of black and Puerto Rican children in dilapidated buildings with the least-experienced and least-qualified teachers. Their schools were so overcrowded that some black children went to school for only part of the day to give others a turn.

The Board of Education appointed a commission to develop a citywide integration plan. But when school officials took some token steps, they faced a wave of white opposition. “It was most intense in the white neighborhoods closest to African American neighborhoods, because they were the ones most likely to be affected by desegregation plans,” says Thomas Sugrue, a historian at New York University and the author of Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North. By the mid-1960s, there were few signs of integration in New York’s schools. In fact, the number of segregated junior-high schools in the city had quadrupled by 1964. That February, civil rights leaders called for a major one-day boycott of the New York City schools. Some 460,000 black and Puerto Rican students stayed home to protest their segregation. It was the largest demonstration for civil rights in the nation’s history. But the boycott upset many white liberals, who thought it was too aggressive, and as thousands of white families fled to the suburbs, the integration campaign collapsed.

Even as New York City was ending its only significant effort to desegregate, the Supreme Court was expanding the Brown ruling. Beginning in the mid-1960s, the court handed down a series of decisions that determined that not only did Brown v. Board allow the use of race to remedy the effects of long-segregated schools, it also required it. Assigning black students to white schools and vice versa was necessary to destroy a system built on racism—even if white families didn’t like it. “All things being equal, with no history of discrimination, it might well be desirable to assign pupils to schools nearest their homes,” the court wrote in its 1971 ruling in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, which upheld busing to desegregate schools in Charlotte, N.C. “But all things are not equal in a system that has been deliberately constructed and maintained to enforce racial segregation. The remedy for such segregation may be administratively awkward, inconvenient and even bizarre in some situations, and may impose burdens on some; but all awkwardness and inconvenience cannot be avoided.”

In what would be an extremely rare and fleeting moment in American history, all three branches of the federal government aligned on the issue. Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, pushed by President Lyndon B. Johnson, which prohibited segregated lunch counters, buses, and parks and allowed the Department of Justice for the first time to sue school districts to force integration. It also gave the government the power to withhold federal funds if the districts did not comply. By 1973, 91 percent of black children in the former Confederate and border states attended school with white children.

But while Northern congressmen embraced efforts to force integration in the South, some balked at efforts to desegregate their own schools. They tucked a passage into the 1964 Civil Rights Act aiming to limit school desegregation in the North by prohibiting school systems from assigning students to schools in order to integrate them unless ordered to do so by a court. Because Northern officials often practiced segregation without the cover of law, it was far less likely that judges would find them in violation of the Constitution.

Not long after, the nation began its retreat from integration. Richard Nixon was elected president in 1968, with the help of a coalition of white voters who opposed integration in housing and schools. He appointed four conservative justices to the Supreme Court and set the stage for a profound legal shift. Since 1974, when the Milliken v. Bradley decision struck down a lower court’s order for a metro-area-wide desegregation program between nearly all-black Detroit city schools and the white suburbs surrounding the city, a series of major Supreme Court rulings on school desegregation have limited the reach of Brown.

When Ronald Reagan became president in 1981, he promoted the notion that using race to integrate schools was just as bad as using race to segregate them. He urged the nation to focus on improving segregated schools by holding them to strict standards, a tacit return to the “separate but equal” doctrine that was roundly rejected in Brown. His administration emphasized that busing and other desegregation programs discriminated against white students. Reagan eliminated federal dollars earmarked to help desegregation and pushed to end hundreds of school-desegregation court orders.

Yet this was the very period when the benefits of integration were becoming most apparent. By 1988, a year after Faraji and I entered middle school, school integration in the United States had reached its peak and the achievement gap between black and white students was at its lowest point since the government began collecting data. The difference in black and white reading scores fell to half what it was in 1971, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics. (As schools have since resegregated, the test-score gap has only grown.) The improvements for black children did not come at the cost of white children. As black test scores rose, so did white ones.

Decades of studies have affirmed integration’s power. A 2010 study released by the Century Foundation found that when children in public housing in Montgomery County, Md., enrolled in middle-class schools, the differences between their scores and those of their wealthier classmates decreased by half in math and a third in reading, and they pulled significantly ahead of their counterparts in poor schools. In fact, integration changes the entire trajectory of black students’ lives. A 2015 longitudinal study by the economist Rucker Johnson at the University of California, Berkeley, followed black adults who had attended desegregated schools and showed that these adults, when compared with their counterparts or even their own siblings in segregated schools, were less likely to be poor, suffer health problems, and go to jail and more likely to go to college and reside in integrated neighborhoods. They even lived longer. Critically, these benefits were passed on to their children while the children of adults who went to segregated schools were more likely to perform poorly in school or drop out.

But integration as a constitutional mandate, as justice for black and Latino children, as a moral righting of past wrongs, is no longer our country’s stated goal. The Supreme Court has effectively sided with Reagan, requiring strict legal colorblindness even if it leaves segregation intact and even striking down desegregation programs that ensured integration for thousands of black students if a single white child did not get into her school of choice. The most recent example was a 2007 case that came to be known as Parents Involved. White parents in Seattle and Jefferson County, Kentu

cky, challenged voluntary integration programs, claiming the districts discriminated against white children by considering race as a factor in apportioning students among schools in order to keep them racially balanced. Five conservative justices struck down these integration plans. In 1968, the court ruled in Green v. County School Board of New Kent County that we should no longer look across a city and see a “ ‘white’ school and a ‘Negro’ school, but just schools.” In 2007, Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. wrote: “Before Brown, schoolchildren were told where they could and could not go to school based on the color of their skin. The school districts in these cases have not carried the heavy burden of demonstrating that we should allow this once again—even for very different reasons.… The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

Legally and culturally, we’ve come to accept segregation once again. Today, across the country, black children are more segregated than they have been at any point in nearly half a century. Except for a few remaining court-ordered desegregation programs, intentional integration almost never occurs unless it’s in the interests of white students. This is even the case in New York City, under the stewardship of Mayor de Blasio, who campaigned by highlighting the city’s racial and economic inequality. De Blasio and his schools chancellor, Carmen Fariña, have acknowledged that they don’t believe their job is to force school integration. “I want to see diversity in schools organically,” Fariña said at a town-hall meeting in Lower Manhattan in February. “I don’t want to see mandates.” The shift in language that trades the word “integration” for “diversity” is critical. Here in this city, as in many, diversity functions as a boutique offering for the children of the privileged but does little to ensure quality education for poor black and Latino children.

“The moral vision behind Brown v. Board of Education is dead,” Ritchie Torres, a city councilman who represents the Bronx and has been pushing the city to address school segregation, told me. Integration, he says, is seen as “something that would be nice to have but not something we need to create a more equitable society. At the same time, we have an intensely segregated school system that is denying a generation of kids of color a fighting chance at a decent life.”

• • •

Najya, of course, had no idea about any of this. She just knew she loved PS 307, waking up each morning excited to head to her pre-K class, where her two best friends were a little black girl named Imani from Farragut and a little white boy named Sam, one of a handful of white pre-K students at the school, with whom we car-pooled from our neighborhood. Four excellent teachers, all of them of color, guided Najya and her classmates with a professionalism and affection that belied the school’s dismal test scores. Faraji and I threw ourselves into the school, joining the parent-teacher association and the school’s leadership team, attending assemblies and chaperoning field trips. We found ourselves relieved at how well things were going. Internally, I started to exhale.

But in the spring of 2015, as Najya’s first year was nearing its end, we read in the news that another elementary school, PS 8, less than a mile from PS 307 in affluent Brooklyn Heights, was plagued by overcrowding. Some students zoned for that school might be rerouted to ours. This made geographic sense. PS 8’s zone was expansive, stretching across Brooklyn Heights under the Manhattan bridge to the Dumbo neighborhood and Vinegar Hill, the neighborhood around PS 307. PS 8’s lines were drawn when most of the development there consisted of factories and warehouses. But gentrification overtook Dumbo, which hugs the East River and provides breathtaking views of the skyline and a quick commute to Manhattan. The largely upper-middle-class and white and Asian children living directly across the street from PS 307 were zoned to the heavily white PS 8.

To accommodate the surging population, PS 8 had turned its drama and dance rooms into general classrooms and cut its pre-K, but it still had to place up to twenty-eight kids in each class. Meanwhile, PS 307 sat at the center of the neighborhood population boom, half empty. Its attendance zone included only the Farragut Houses and was one of the tiniest in the city. Because Farragut residents were aging, with dwindling numbers of school-age children, PS 307 was underenrolled.

In early spring 2015, the city’s Department of Education sent out notices telling fifty families that had applied to kindergarten at PS 8 that their children would be placed on the waiting list and instead guaranteed admission to PS 307. Distraught parents dashed off letters to school administrators and to their elected officials. They pleaded their case to the press. “We bought a home here, and one of the main reasons was because it was known that kindergarten admissions [at PS 8] were pretty much guaranteed,” one parent told the New York Post, adding that he wouldn’t send his child to PS 307. Another parent whose twins had secured coveted spots made the objections to PS 307 more plain: “I would be concerned about safety,” he said. “I don’t hear good things about that school.”

That May, as I sat at a meeting that PS 8 parents arranged with school officials, I was struck by the sheer power these parents had drawn into that auditorium. This meeting about the overcrowding at PS 8, which involved fifty children in a system of more than one million, had summoned a state senator, a state assemblywoman, a City Council member, the city comptroller and the staff members of several other elected officials. It had rarely been clearer to me how segregation and integration, at their core, are about power and who gets access to it. As the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in 1967: “I cannot see how the Negro will totally be liberated from the crushing weight of poor education, squalid housing and economic strangulation until he is integrated, with power, into every level of American life.”

As the politicians looked on, two white fathers gave an impassioned PowerPoint presentation in which they asked the Department of Education to place more children into already-teeming classrooms rather than send kids zoned to PS 8 to PS 307. Another speaker, whose child had been wait-listed, choked up as he talked about having to break it to his kindergarten-age son that he would not be able to go to school with the children with whom he’d shared play dates and Sunday dinners. “We haven’t told him yet” that he didn’t get into PS 8, the father said, as eyes in the crowd grew misty. “We hope to never have to tell him.”

The meeting was emotional and at times angry, with parents shouting out their anxieties about safety and low test scores at PS 307. But the concerns they voiced may have also masked something else. While suburban parents, who are mostly white, say they are selecting schools based on test scores, the racial makeup of a school actually plays a larger role in their school decisions, according to a 2009 study published in The American Journal of Education. Amy Stuart Wells, a professor of sociology and education at Columbia University’s Teachers College, found the same thing when she studied how white parents choose schools in New York City. “In a postracial era, we don’t have to say it’s about race or the color of the kids in the building,” Wells told me. “We can concentrate poverty and kids of color and then fail to provide the resources to support and sustain those schools, and then we can see a school full of black kids and then say, ‘Oh, look at their test scores.’ It’s all very tidy now, this whole system.”

I left that meeting upset about how PS 307 had been characterized, but I didn’t give it much thought again until the end of summer, when Najya was about to start kindergarten. I heard that the community education council was holding a meeting to discuss a potential rezoning of PS 8 and PS 307. The council, an elected group that oversees twenty-eight public schools in District 13, including PS 8 and PS 307, is responsible for approving zoning decisions. School was still out for the summer, and almost no PS 307 parents knew plans were underway that could affect them. At the meeting, two men from the school system’s Office of District Planning projected a rezoning map onto a screen. The plan would split the PS 8 zone roughly in half, divided by the Brooklyn Bridge. It would turn PS 8 into the exclusive neighborhood school for Brooklyn Height

s and reroute Dumbo and Vinegar Hill students to PS 307. A tall, white man with brown hair that flopped over his forehead said he was from Concord Village, a complex that should have fallen on the 307 side of the line. He thanked the council for producing a plan that reflected his neighbors’ concerns by keeping his complex in the PS 8 zone. It became clear that while parents in Farragut, Dumbo, and Vinegar Hill had not even known about the rezoning plan, some residents had organized and lobbied to influence how the lines were drawn.

The officials presented the rezoning plan, which would affect incoming kindergartners, as beneficial to everyone. If the children in the part of the zone newly assigned to PS 307 enrolled at the school, PS 8’s overcrowding would be relieved at least temporarily. And PS 307, the officials’ presentation showed, would fill its empty seats with white children and give all the school’s students that most elusive thing: integration.

• • •

It was hard not to be skeptical about the department’s plan. New York, like many deeply segregated cities, has a terrible track record of maintaining racial balance in formerly underenrolled segregated schools once white families come in. Schools like PS 321 in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood and the Academy of Arts and Letters in Fort Greene tend to go through a brief period of transitional integration, in which significant numbers of white students enroll, and then the numbers of Latino and black students dwindle. In fact, that’s exactly what happened at PS 8.

A decade ago, PS 8 was PS 307’s mirror image. Predominantly filled with low-income black and Latino students from surrounding neighborhoods, PS 8, with its low test scores and low enrollment, languished amid a community of affluence because white parents in the neighborhood refused to send their children there. A group of parents worked hard with school administrators to turn the school around, writing grants to start programs for art and other enrichment activities. Then more white and Asian parents started to enroll their children. One of them was David Goldsmith, who later became president of the community education council tasked with considering the rezoning of PS 8 and PS 307. Goldsmith is white and, at the time, lived in Vinegar Hill with his Filipino wife and their daughter.

The Best American Magazine Writing 2020

The Best American Magazine Writing 2020 The Best American Magazine Writing 2016

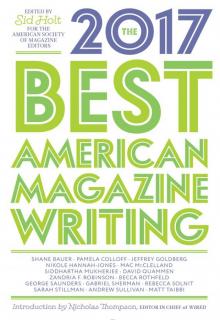

The Best American Magazine Writing 2016 The Best American Magazine Writing 2017

The Best American Magazine Writing 2017